The summer palace of the Rajputana royals of Rajasthan boasts of the iconic honeycombed windows known as jharokhas. Dubbed the Hawa Mahal as a nod to the engineered airflow and ventilation system, the residence seems to hover above ground over the Badi Chaupar area in the Pink City. With its unique red-pink sandstone exterior and stone arches, this Mughal-Rajput fusion architecture is a bastion of heritage in Jaipur– synchronously serving as a memoir of social invisibility.

Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh: Kachwaha Ruler of Jaipur

Built in the year 1799 by Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh, it was architect Lal Chand Usta who designed the famed latticed windows of the Hawa Mahal. The rationale for building this pyramidal structure with 953 casements is no secret today, as the purpose served by the jharokhas has been well documented over time. The palace itself is situated on the edge of the City Palace, extending into the women’s quarters, or the zenana. The window acts as a membrane between women and visibility; in order to understand its significance in India, one needs to go back in time.

With the expansion of the Mughal rule in India, certain Islamic customs practiced by the nobility entered the domain of upper-class Hindu households. One of these was the purdah system– the sociocultural practice of concealment of women either through physical veiling, or the demarcation of inner and outer domains. The inner worlds of the home and hearth were the designated feminine spaces, powerfully punctuated by the threshold beyond where the public space of men spread out indefinitely.

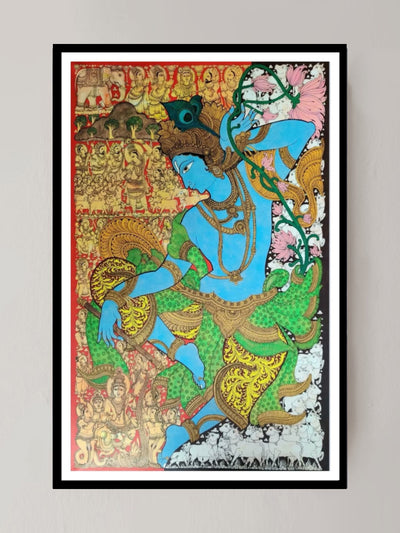

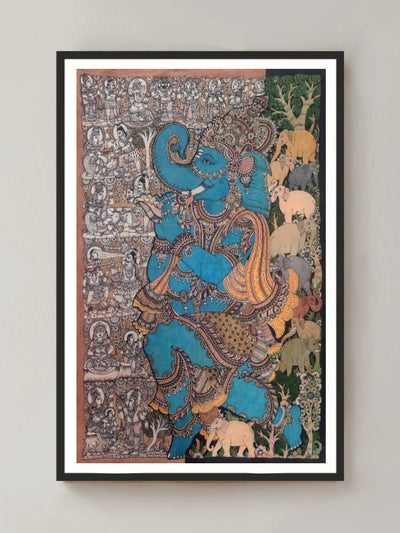

A Rendition of Old Jaipur

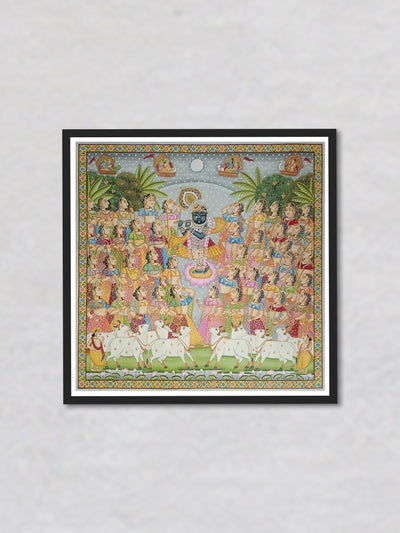

It was with this dichotomy in mind that Sawai Pratap Singh had the Hawa Mahal constructed for the royal women of the palace. The latticed jharokhas, beautiful as they are, operated as a one-way window onto the outside world. This guaranteed the privacy – and invisibility – of the women while also allowing them to gaze upon the goings-on of Jaipur city. The membrane itself was like a threshold – safely within the circuit of the home, but providing a glimpse (and sense of participation) into the world outside. Rajput women of high birth led their own rich lives populated with private interests and courtly intrigues within the zenana. However, they were so divorced from the general populace (and arguably, social reality) that in theory, their existence seems to be a fabular web of myths and folklore.

Of course, this is not to say that the cage itself was not gilded with the best of riches. The Hawa Mahal has sunny courtyards adorned with founts of cool, fresh water; the floors are composed of luxurious coloured marble; the windows inlaid with stained glass transform the rooms into prisms of magical delight. One might argue that when the interior realm is a gem-studded wonder of filtered light and comfort, it is a mark of privilege to be protected from the sun’s harsh glare outside. However, decadence does not make up for historical erasure.

Inside the Hawa Mahal

Roughly three to four decades after the construction of the Mahal, it was another Maharaja of Jaipur who overturned this rhetoric of invisibility in a move that was considered extremely radical at the time. The introduction of the camera obscura to the Indian subcontinent had piqued the curiosity of many members of royalty. Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II was one of them, and he used the device unlike any other before him.

According to acclaimed historian Manu S Pillai, “While princes across India developed a fondness for photography, few mastered it in the way he did — or created a collection that so encapsulated a world in which the Victorian and the Indian met constructively.”

Unidentified Woman of the Royal Zenana: Photographed by Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II

References

- Weinstein, Laura, “Exposing the Zenana: Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II’s Photographs of Women in Purdah”

- https://jacdigital.shorthandstories.com/TheIndianWoman/index.html

- https://www.whatshot.in/jaipur/the-unique-story-behind-hawa-mahals-953-jharokhas-that-blend-mughal--rajput-architecture-c-34521

- https://www.vibeindian.in/hawa-mahal/

- https://pinkcity.com/places-to-visit/city-palace/zenana-mahal-inside-city-palace/

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/art-and-culture/this-jaipur-king-so-loved-photography-he-even-took-photos-in-the-zenana/story-YYnvUmiuuwFVcY5XnNVYJI.html

- https://inbreakthrough.org/purdah-system-history/

0 comments