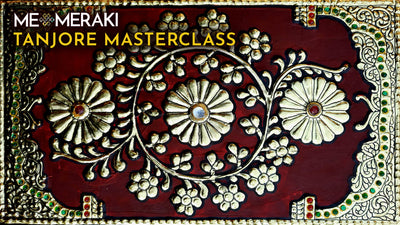

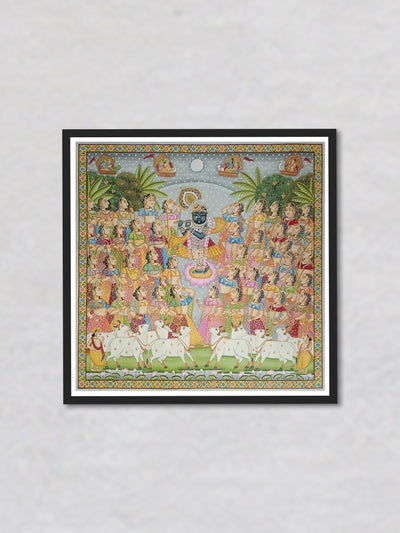

Shimmering with gold foil and precious gemstones, the divine depictions of Thanjavur paintings have been a sight to behold for centuries, preserving the rich cultural heritage of Tamil Nadu in all its glory.

Established under the patronage of Nayaka and Maratha rulers of Thanjavur, this painting school flourished in the late 17th to 19th centuries. With the Geographical Indication (GI) tag bestowed upon Thanjavur paintings in 2007, this traditional Indian art form has received a renewed surge of commercial interest. A geographical indication is a hallmark issued by the Geographical Indication Registry under the Department of Industry Promotion and Internal Trad to safeguard the regional heritage and promote local economies. With its authenticity protected and its origins recognized, Thanjavur paintings once again became a source of awe and inspiration for art lovers worldwide in the 21st century.

With time and technology, artists have introduced several variations in this painting form. Moreover, cost, ease of material availability, and artistic preferences continue to shape the aesthetics and traditions of Thanjavur art. By uncovering the modern status of Thanjavur paintings, this article paints a vivid portrait of the enduring legacy of this timeless art.

Modernization of Materials & Methods

Thanjavur paintings are typically designed to be hung on walls and viewed from afar. They are generally made on wooden panels wrapped in cloth, which gives them the Tamil name of palagai padam, meaning “pictures on wood”. The wood is usually pazha maram (jackfruit) or teakwood because it does not invite termites or rot quickly. The craft of traditional Thanjavur paintings is an intricate process involving multiple steps. It starts with stretching cotton cloth over the wooden panels using Arabic gum or kezhangu passai (indigenous gum). With the help of a metal blade, the artist scrapes on the pasted cloth to remove air bubbles. Once the cloth is dry, a mixture of tamarind seed and chalk powder is applied as a top layer and left to dry. When the paste has been set, the surface is polished with a sandpaper sheet to achieve a smooth and flawless finish. According to an acclaimed practitioner and certified teacher of Thanjavur paintings, L Ramanujam, “The kernel of the tamarind seed, when soaked, acts as an adhesive. The husk helps to create a protective layer for the cloth and wood.” Today, many artists also use chart paper instead of cloth, and there are easy water-soluble adhesive options like Fevicol. But traditionally, the tamarind seed paste and cotton cloth are scientific material choices to protect the painting from insects and prolong its life.

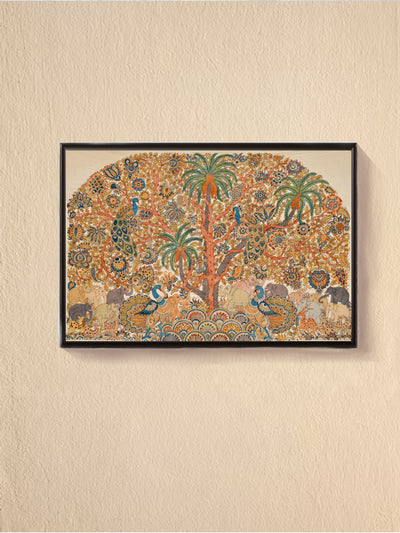

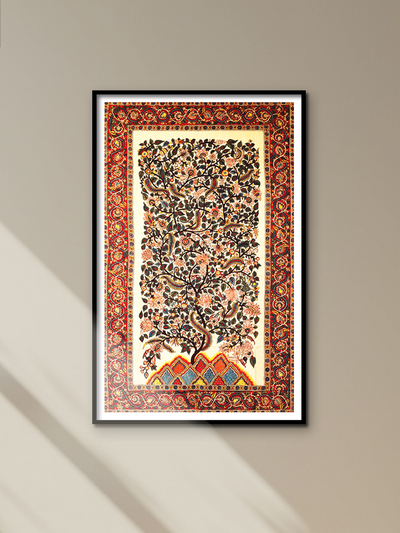

Next, the subject of the painting and the background are either drawn or marked on the board with mai (soot) from a vellakennai lamp through anil vaal (squirrel tail hair) brush. For the relief work called the gesso technique, the hallmark of Thanjavur paintings, a gesso paste made of a 2:1 ratio of chalk powder and indigenous gum is applied on the selected areas like jewellery costumes, architectural arches using a brush or a squeezing bottle. Gems or stones are then embedded, and gold paper is added for a stunning, embossed effect using the pointed end of a paintbrush. Intricate details are coloured first, followed by the background with deep greens, blues, or reds, while the central figures are executed in white, yellow, green, or blue. In the past, natural pigments extracted from sources like vegetables, leaves, roots, and bark were used, but modern Thanjavur paintings feature heavier gold work and richer hues from artificial colours.

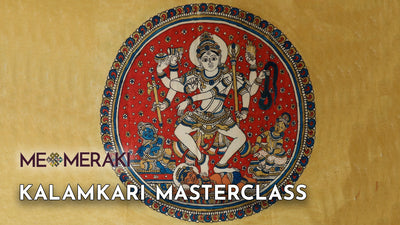

Materials Lesson from the MeMeraki Tanjore Masterclass

As Thanjavur paintings gained commercial popularity, the modernization of materials and techniques became inevitable. Originally created for worship, these stunning works of art would now last for generations if preserved and displayed correctly. But waterproof ply boards, adhesive and acrylic paint have replaced their natural, durable predecessors. Modern machine-made brushes have taken over from ethnic brushes made with tiny bunches of squirrel fur threaded through the bony ends of pigeon and eagle feathers secured with bamboo flints. “[In earlier days,] artists have also painted with Thazhampoo (screw pine flower) and the edges of bamboo fans,” as L Ramanujam claims. A contemporary painter now uses poster colours instead of vegetable dyes and mai (lamp-black from soot), gilt instead of gold, and glass bits instead of rare and precious stones.

But several people also try to retain the traditions. Meena Muthiah, who runs a Tanjore painting school in Madras, still tries to stick to gold and traditions as much as possible. But most cannot afford it, and the nouveau riche buyer may insist on something other than the traditional style. L Ramanujam also believes keeping technology at a minimum is essential when teaching this artist. “Drawing manually helps the hands and imagination to work in tandem, which is missing when one uses photo-editing software,” he says.

MeMeraki Tanjore Masterclass Art Kit

It is fascinating to witness the modern improvisation of artists in this form of painting and realize that the love for gold has endured. Culturally, in Southern Indian households, gold is a symbol of purity and is considered auspicious due to its non-reactive properties. It has a strong ritualistic significance in the Hindu religion. As a result, gold has been a form of social currency and an emblem of prosperity for centuries. Thus, it is natural that expensive gold leaf is still applied to some of these works, even if the cheaper gold paper is widely used for embossing.

Contemporary Flair on Classical Themes

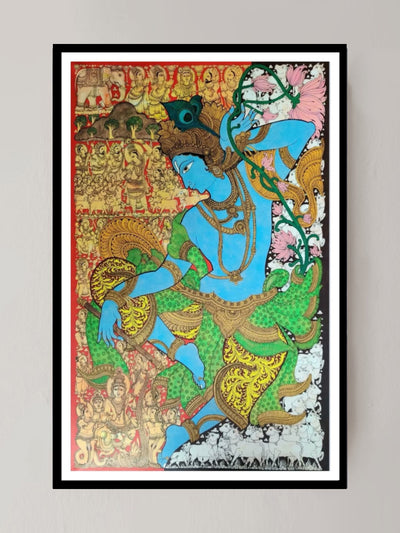

In recent times, Thanjavur artists have been exploring new themes and styles. Srinvasulu, Head of the Painting Department at Kalakshetra, seeks to introduce secular themes and elements of folk art into the iconic Thanjavur style. Religious Thanjavur paintings have also undergone considerable change. Glossy, polished images of deities like Krishna, with cherubic forms and gilded decoration (impact of the Nayaka paintings), were produced for the mass market. Static poses gave way to more three-dimensional perspectives with some influence from Western academic realism.

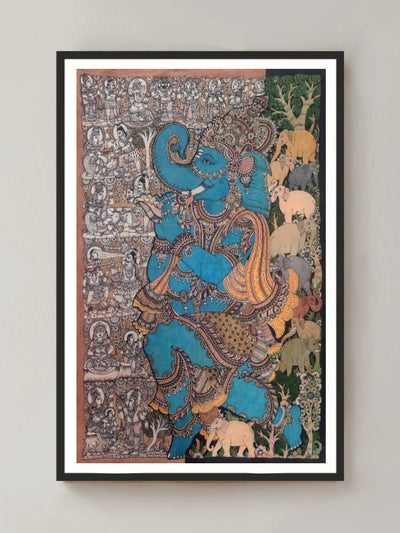

Balaji Srinivasan, a renowned artist, draws inspiration from Thanjavur paintings while bringing innovation to his work. He explores ancient texts to achieve compositional harmony and incorporates classical features like decorative gold ornamentation and stylized eyes into his paintings. In his work, such as the painting Punnaimarakkannan (Krishna under the Cypress tree), he follows the Chitra sutras with subtle variations of namarupas (name-designated figures). However, his ‘modern’ pieces, like Metamorphosis, combine Jain and Shaivite iconography to depict the song of the Mahamudra, which symbolizes the nine stages of the mind. Another painting, Arasilai (Pipal leaf), merges Sri Yantra (a geometric figure representing the feminine principle) in the background with Lajja Gowri, who represents the cosmic mother in her bloom in Indian tantric traditions.

Metamorphosis by Balaji Srinivasan (Source - arjuna-vallabha.tumblr.com)

Thanjavur artists are now expected to embrace entrepreneurial innovation and adapt to market realities. However, some are hesitant to modify their designs. The architectural aspects, inspired by ancient temples, understandably remain constant. Similarly, the jewellery on the gods and other religious iconography holds spiritual significance and has little scope for contemporary innovations. According to historian Jaya Appasamy, the iconic style of Thanjavur painting served a functional purpose for worship rather than being solely decorative. Thus, its repetitive themes can be attributed to its sacredness.

From Tradition to Trend: The Commercialization of Thanjavur Paintings

While the GI Tag ignited a new-found love for this art, relatively cheaper fake gold foil flooded the art market, aiding insincere profit motives. Due to commercialization, they are found in prayer rooms, attics, plush drawing rooms, and corporate offices. Dealers have emerged in Madras, scouring traditional centers for originals in Thanjavur, Trichy, and Karaikudi. Antique paintings, priced between Rs 25,000 and Rs 2 lakh, are in high demand, leading to frequent exhibitions and sales in the four metros. However, as supply falls short, imitations are being produced and sold.

As the value of Thanjavur art becomes more widely recognized, households are increasingly seeking out dealers to sell their paintings. However, dealers often rely on intermediaries in rural Tamil Nadu, who purchase the pictures for a fraction of their worth. As the pictures pass through multiple hands and reach the final buyer, their price increases significantly.

Although affluent and overseas buyers do not mind paying high prices, artists also cater to the market’s budgetary needs. While they prefer to maintain their artistic integrity, they are also willing to offer cheaper alternatives. For instance, Swaminathan Vishwakarma has a price chart on his social media pages, managed by his graphic designer son. His paintings with original gold cost Rs. 4,500 for a 12 x 10 size, while the same size with “second quality” gold is cheaper by Rs. 1,000. As the size increases, the price difference compounds. A 4 feet x 3 feet work with pure gold foil costs Rs. 1,20,000, while the second quality version costs Rs. 80,000.

In 1990, Ramachandra Raju from Indian Crafts stated that while an old Tanjore painting yields a 15-20% profit, a new one generates a clean 50% profit. Although Raju established the business in 1952, the gallery on Mount Road was opened in the late 90s. He admitted that imitations bring in money, while selling original paintings to celebrities, consulates, five-star hotels, and top companies brings prestige. Meena Muthiah expressed dismay that some people ask for a Thanjavur painting for as low as Rs 200. Some dealers fulfill such requests by creating garish images adorned with confetti, coloured beads, and aluminum foil.

Thanjavur Painting Workshop

The future seems bright for Thanjavur painting as various promising initiatives are being taken to promote this traditional art.

In 2011, a four-day training workshop was organized at the Government Museum on International Museum Day. The training was exclusively for women, and about 35 women, primarily homemakers, learned simple techniques of Thanjavur painting free of cost. Certificates were awarded to the participants on the concluding day of the event. M. Rajappa, the resource person, taught the trainees the principles of selecting stones for specific zones and fixing gold leaves.

In 2013, a one-year training course on Thanjavur painting in Srirangam received an overwhelming response from women in Trichy and neighboring districts. The course had 100 students trained in the art form for a year. The Tamil Nadu Handicrafts Development Corporation opened admissions, and 440 applications were issued. The scheme has been hailed as a boon for talented women as the trainees get a stipend of Rs 2,000 per month.

At Thanjavur Art Gallery on Amma Mandapam Road in Srirangam, L Ramanujam runs a training school where more than 2,000 students from the State and abroad have graduated from his 50-class courses. He started his certificate art course under the auspices of the District Industries Centre in 1980, focusing on training women. He believes that this art form can be easily incorporated into the daily routine of homemakers and can help women become financially independent. The course teaches students how to make Thanjavur paintings on Hindu, Christian, and Islamic themes.

Due to the surge in demand, several schools have emerged, offering to teach the art of Thanjavur painting. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, online workshops and courses allowed people to adopt this traditional art form.

Overall, Thanjavur art is a remarkable bridge between the past and present, seamlessly blending traditional and modern elements to elevate Indian art to unprecedented levels. Through this approach, the cultural heritage of Thanjavur remains a living legacy, simultaneously evolving and adapting to contemporary artistic expressions.

References

Appasamy, Jaya. Thanjavur Painting of the Maratha Period. Abhinav Publication, 1980.

Tanjore: The Traditional Painting of South India - Authindia

Suddenly, traditional Tanjore school is immensely popular

Women queue up to learn Thanjavur painting | Coimbatore News - Times of India

0 comments